Look Back at Marvel's Trading Cards of the 90’s

Dan Buckley and Michael Pasciullo give the inside story of one of Marvel's most impactful initiatives of the 1990's!

Ask just many creators or fans who grew up in the 90’s where they found out about Marvel characters for the first time and you’ll find one recurring answer: trading cards.

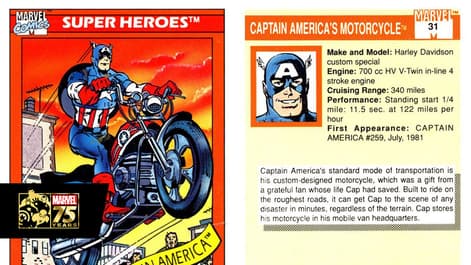

Before the days when you could look anyone up on the Internet, legions of fans got their information from the various card sets produced in the 90’s. Each came with unique, one-of-a-kind artwork on the front and a variety of offerings on the back from stats and biographies to full comic stories and even additional artwork.

It all started in 1990 with the launch of the Marvel Universe trading cards from a company called Impel that would rebrand itself as SkyBox in 1992. That same year, Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. purchased Fleer which then bought out SkyBox in 1995. By 1999, Marvel sold the Fleer-Skybox brand off, but in that time a variety of comic-based trading cards found their way into fans’ hands.

The sets branched out to focus on subsections of the Marvel Universe, large events, and even artist-centric collections done by the likes of Andy and Adam Kubert. To celebrate the sets that influenced a whole generation, Marvel.com talked with current Marvel President & Publisher – Print, TV & Digital Dan Buckley, and SVP, Marketing, Marvel Studios & Television Michael Pasciullo who both worked on the sets back then as Business Unit Director and Assistant Marketing Manager respectively.

So how did they get into the game? Buckley moved over to the card company after his first stint at Marvel and worked with future Marvel Executive Vice President Bill Jemas.

“[Jemas] was running all the trading card business at Fleer at that time,” Buckley says. “Marvel had acquired Fleer. The Marvel trading card license was originally with Skybox. When the Skybox license ran out, Fleer started making Marvel trading cards. Bill Jemas was the guy who did that. Business was booming. He was going to be in charge of more things and he asked me if I wanted to take over the trading card business for Fleer for Marvel.”

Marvel Universe Series I card

For his part, Pasciullo, then a recent college graduate with a marketing degree, responded to a job ad without even knowing what it was for.

“One Sunday, I opened up the ‘Philadelphia Inquirer’ and there was a job posting that only said they were looking for someone with a college degree and a knowledge of Marvel Comics,” he recalls. “So I sent in my resume and ended up getting a call for an interview with Fleer. At that time, Bill Jemas was in charge of Fleer so my interview was with him in his office. I’ll never forget that at the end of the interview he pointed at the Marvel Universe poster by Ed Hannigan that he had on his wall and said that he was going to point to 10 characters and that I needed to identify which characters they were. Fortunately, I went 10 for 10.”

Both Buckley and Pasciullo had a hand in developing card sets, as well as who would draw them and what would show up on the back.

“I was involved in product development and marketing,” Pasciullo says. “From a product development standpoint, I was involved with developing what the trading card sets would be, the different themes/sections within the sets, the artists that would be used, the design of the cards and the writing and proofreading of the cards. From a marketing standpoint, it was the advertising and messaging to retailers as well as to consumers which included sales materials, packaging, giveaways, and events.”

“I love planning trading card sets because you just do maybe five or six a year and you lay them out over a year,” Buckley says. “It was a group of maybe five, six, seven of us. We sit in a room and talk about who we think are the artists that we’d want to get to do certain work and then our production guy Jim Boyle would say, ‘I think I could do this with foil. I could do this hole.’ We’d talk about the lead times associated with those things. And you could nail down the plans for trading card sets over a one to two week period for a year and it took a lot longer to get them together with the artist.”

“It almost became a game to see how deep into the well you could go,” Pasciullo explains. “But the best part was that this was about two years before the Internet hit, so we were doing this all from our own personal reading experiences. You couldn’t simply Google ‘Spider-Man Villains.’ Instead it was about remembering how cool it was when Spot showed up for the first time in an issue of PETER PARKER, THE SENSATIONAL SPIDER-MAN.”

Marvel Universe Series II packaging

The sets themselves would revolve around the most popular comics, series and events of the day. At the time, the X-Men and Spider-Man not only sold well in shops, but also starred in animated series and action figure lines, so they were clear choices. Meanwhile, the Marvel Masterpiece sets offered more painterly interpretations of the characters.

“Obviously in that day and age you knew you were going to do a Spider-Man trading card set and you’d do an X-Men one,” Buckley notes. “You’d probably do some sort of Marvel Universe one and then you might think about some hot artists or fine artists that you would probably plug into Masterpiece because it was a viable trading card brand or franchise or whatever you want to call it. So we look at those things and say, ‘Well, Spider-Man. What do you think the hook is?’ And it may have been a timeline or it might have been a comic book story on the backs. You come up with a couple of different editorial technological hooks and then you start looking at stuff that’s in nines because that’s how the trading card binders lined up.”

“The fun came in deciding which characters would then be featured in those sets,” Pasciullo says. “For the Marvel Universe sets, it was fairly straightforward because there were so many popular characters in the Marvel Universe that you could easily fill up a 150 card set without breaking a sweat. It was when we worked on the Spider-Man and X-Men sets that we really got to channel our inner fanboy. Early on, there was a small group of us including Steve Domzalski, Ben Plavin, Ron Perazza, and eventually Dan Buckley that would sit around and come up with any characters from those families that we could remember from all the comic books that we had read throughout our lives.”

Once the group figured out which characters would go in which sets, they hired artists to draw those classic pin-ups.

“The artists loved working on the trading card series for two very simple reasons: one, it was easier and faster to draw a trading card than a comic book and, two, they were paid very, very, very well,” Pasciullo says. “Marvel trading cards during the mid-to-late 90’s was a very successful and profitable business so we could afford to get the best artists and pay them well. I know one artist that bought a house from just the work he did on trading cards. As far as how they were chosen, we had an amazing art director named Jennifer Caudill who was always looking both within the comic book industry as well as outside of it for great artists. Some of the coolest pieces we made were done by artists that had never drawn or painted a comic book. Some of the artists that, if I remember correctly, had not worked in comics that did some amazing work for us were Dave DeVries, Peter Bollinger, Mark Fredrickson and Marc Sasso.”

Marvel Masterpiece cards

“You would probably look at artists and look at groups of what you could put together and so you try to line up artists to do things along that line,” Buckley continues. “Masterpieces you would definitely look for artists. There were four guys and that was the artistic approach. You kind of went to those guys and said, ‘How much work can you do in a certain timeline?’ and you negotiate a rate. If they were interested finances usually weren’t an issue. They were paid pretty well.”

With the front of the cards figured out, the next step was deciding what exactly would go on the back.

“That process was part Marvel, part personal knowledge and part research,” Pasciullo says. “And by ‘research,’ that meant either going into our own personal comic book collections to find information or going to the comic book store down the street from the office to see if they had the issues that we would need; try coming up with pertinent and factual information about Stegron without the aid of a Wiki.”

Considering the sheer number of offerings, the focus of the card backs shifted from passing along specific information to figuring out new ways to use that side of the card as a way to draw in collectors.

“We were doing a lot of cards so it got harder to find what was going to be cool, new information you could give to somebody every year,” Buckley admits. “That’s why you saw a lot of the card backs turn into artist collections too. I think the last Spider-Man set that I was involved in doing we did two [things] that were pretty unique. One, I think that was the first trading card set where we did original art cards. We did like little mini blue boards and guys drew stuff. That’s pretty prevalent now.

“I think the core collection [for that set] had a John Romita piece where if you put them all together it would make one big John Romita poster. Then we had a John Romita Jr. piece that was a two box chase and that was post-wedding. It had a wedding picture in it and that was pretty neat. We did a Wolverine trading card set and it was actually an in continuity comic book.”

Fleer Ultra X-Men cards

Pasciullo recalls a few instances when trying to keep the cards fresh and interesting might have gone a little too far:

“I remember for the ’94 Fleer Ultra X-Men set, we created a subset called Spring Break that was actually the X-Men in bathing suits hanging at the beach. There was a card where Wolverine was literally using his claws to cook hot dogs. And for the ’95 Fleer Ultra Spider-Man set, we did a subset called Carnage U.S.A. that was basically depictions of Carnage destroying national landmarks on the front and the back of the cards were postcards detailing the destruction that he sent back to various people from the Spider-Man family of characters. We didn’t clear either of those sets with Marvel and when they saw them in for the first time, they were not too happy with us.

But I think we may have finally and completely crossed the line when we did the subset called Asylum in the Spider-Man Premium ’96 card set. The premise was that the villains were in an Asylum and the back of the cards were written in their crazed voices. For the Venom card, I decided to have Venom write his own lyrics to the classic Spider-Man song. After going method by sitting in a dark office by myself for half a day, I came up with ‘Spider-Man, Spider-Man, Squashed like only a Spider can, Eat his brains, drink his blood, Chew him up just like chum, Look out, I’ll eat a Spider-Man!’ Somehow, most of that actually made it to the back of the card.”

Buckley fondly looks back on the line of cards based on the Marvel Vs. DC Comics crossover and the ensuing Amalgam mash-up comics.

“That [was] nutty to do,” he remembers. “I remember sitting in the meeting and we had to work on a very expedited timeline. That’s why if you ever look at the trading cards the checklist is relatively short. Usually your core artwork is 100 cards and then you have some chase. That was 72, I think, the core set. The main reason is because you only could hire the artists who were drawing the books because they were the only people who knew what the characters looked like.

“If anyone has taken the time to read those card backs that is probably the best card back set we ever did because that’s where we actually did mash-ups of continuity as if that comic book imprint and universe existed. So we worked with the editorial groups at Marvel and DC. For example, one of the card backs would have had Infinite Secret Wars. So that was actually a very fun editorial one to do. We did that card set in half the time we did any other card set.”

Fleer Ultra Spider-Man cards

Looking back, Buckley and Pasciullo each point out additional reasons why the comic book cards did so well in the 90’s, one involving artwork quality, the other Major League Baseball.

“There was a window there where the trading cards offered something that you couldn’t get elsewhere because the economics and the production processes were different,” Buckley says. “And the production technologies for comics had not changed yet when this was happening. So [for] the trading cards, a lot of guys were able to do a lot of painted work, a lot of computer-colored work, a lot of high end painted and computer-colored stuff that wasn’t part of what you saw in comics yet. So the trading cards had a distinctly different artistic presentation than what you saw in the books.”

“One other important thing to remember is that in the summer of 1994, there was a MLB players strike that ended the season in August which not only hampered the ability to do baseball cards but it also drove away many baseball fans and card collectors,” Pasciullo adds. “Even when the strike was over, many of them were so upset with the league and the players that they did not come back to the sport or the hobby.”

The sports collecting world’s loss proved the comic industry’s gain as these card sets not only brought in fans, but also new and interesting variant cover options.

“Jim Boyle, who is in charge of printing for Marvel Comics now, was in charge of Fleer’s printing and production back then and he was always ahead of the curve with technologies and printing capabilities,” Pasciullo says. “He was always pushing the envelope to make sure we were doing the next cool thing. I think Marvel ended up taking some of his ideas and using them for covers as well. And from a scarcity or chase perspective, I think the comic book industry definitely took notice and saw how lucrative it could be. By no means did we invent it—I’m not taking the responsibility/blame for that—but I think we helped influence and perpetuate the variant trend.”

Pasciullo and Buckley both look back proudly on their time making Marvel cards not only for the personal challenges and experience, but also the products they created and the influence they had on the industry.

Marvel Universe 1994 cards

“I never really thought about it from that context but my time at Fleer is something that I am very proud of and grateful for,” Pasciullo reflects. “I’ll be honest, when I started at Fleer, I was a few months out of college and still going to the comic book store every Friday to get my comic books—yes, back in the 90’s comic books actually came out on Fridays. I knew that I would never work at Marvel but this was my chance to be a part of and create something new for Marvel, to be part of, albeit a small part, of the Marvel tradition. If the stuff that we worked on back then has influenced people that much, then that just makes the entire experience that much cooler.”

“Going back and looking, it was just interesting to see the range of people you could get to do the work,” Buckley concludes. “Editorially, I was proud of what we did.”

The Hype Box

Can’t-miss news and updates from across the Marvel Universe!