The Atlas Era: Before Marvel Became Marvel

Throughout the 1950s, Atlas Comics paved the way for Marvel and began the stories of some of its most classic characters.

For a brief seven-year period in the 1950s, publisher Martin Goodman’s Atlas Comics weathered the comics industry’s many storms to chart a course for its inheritor, Marvel Comics, to inaugurate a bold new era of innovation and creativity.

Goodman had already spent the 1940s riding popular publishing trends as Timely Comics, but by 1951 launched his own distribution company to expand his empire ever more. The name “Atlas” came about ostensibly to brand his distribution, but grew to represent his comics informally. As the decade progressed, more and more titles began to sport the recognizable “globe” symbol and the name proliferated.

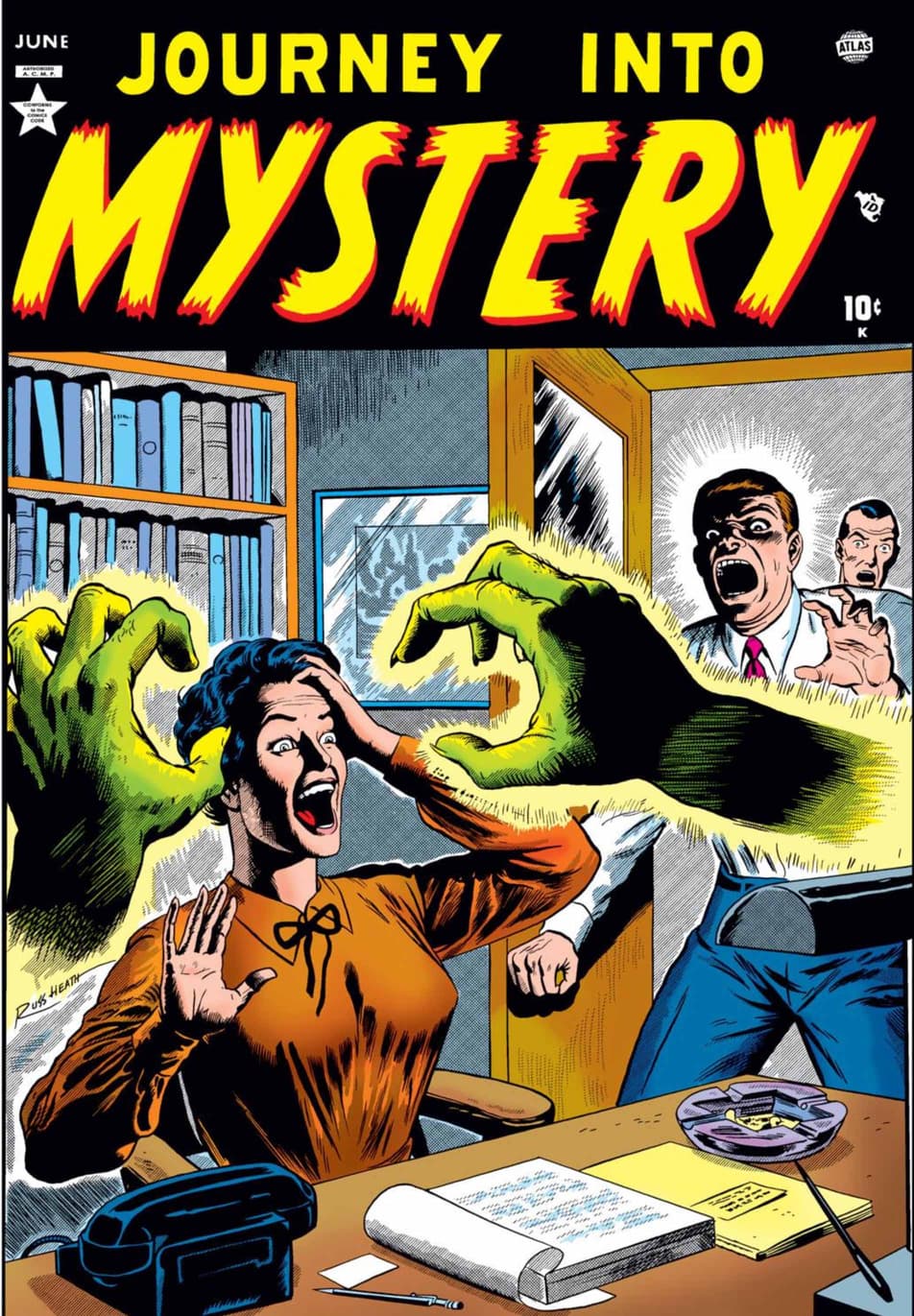

While the Korean War raged overseas and the Super Heroes of World War II fell into disregard, Goodman continued to flood the market with comics in every conceivable genre. Looking at a 1952 newsstand, one would see an incredible array of Atlas titles that offered horror, romance, war, crime, Western, teen humor, funny animals, and sports stories. Hero books like the once-popular VENUS were cancelled to make way for Goodman to try a science fiction-fantasy comic like JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY.

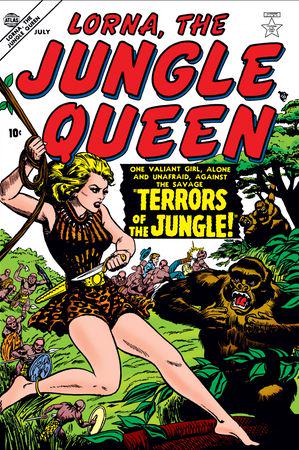

Around this time, a psychiatrist named Frederic Wertham found a bully pulpit to broadcast his disdain for comics and fear for what he perceived as their baneful effect on children. Though Goodman made some small effort to quell any parents’ concerns in 1953, his own focus fell to experimenting with such books as LORNA THE JUNGLE QUEEN, BIBLE TALES FOR YOUNG FOLKS, SPEED CARTER SPACEMAN, and CRAZY, Atlas’ answer to the new trend in humor comics exemplified by MAD MAGAZINE.

Goodman also relaunched what was once his best-selling triumvirate of Super Heroes, the Human Torch, Namor the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America in YOUNG MEN #24 in hopes the time had come again for costumed crimebusters. Despite good intentions, the three characters went down in flames once more despite revivals of each of their individual titles in 1954. Perhaps they sensed the thundercloud about to burst in the form of Wertham’s “Seduction of the Innocent,” a book detailing comic books’ “seduction” of youngsters to crime, violence, and worse. While Atlas continued to publish more and more titles, a Senate subcommittee spurred on by the psychiatrist’s tongue-lashing of the industry nearly brought the entire works to a halt with hearings to determine how much of what Wertham’s diatribe was true.

By the end of 1955, the comic book playing field looked very different than when the year began. Goodman and other publishers set up a self-policing system called the Comics Code Authority to regulate just how much horror, romance, and crime could be shown in the panels of a typical story. Atlas continued to produce books, but toned down its titles to appease the Code and parents. As the year came to close, Goodman had decidedly less competition due to comic company closures across the board, and picked up several writers and artists looking for work. Together they dreamed up new themes like the medieval adventures in BLACK KNIGHT, relied on old standbys such as Westerns in RAWHIDE KID and WYATT EARP, and took stock of the arrival of the terrifying titan called television.

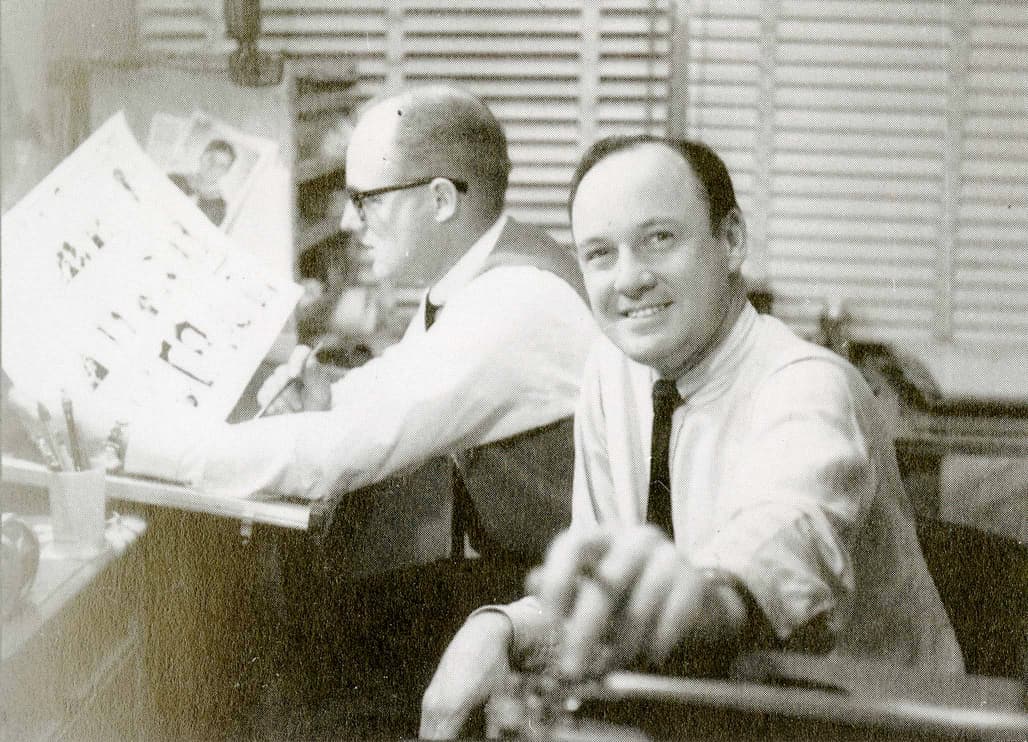

Everything changed again in 1956, or perhaps it’s better to say things grew worse. The industry shrank dynamically, but Atlas chugged ahead, driven by Martin Goodman’s desire to stay in business. In an attempt to hunker down, he announced cutbacks on new work to his editor, Stan Lee (pictured above, right, with artist Joe Maneely, left), and lowered page rates across the board. While a bigger company like National found success that year in bringing back Super Heroes and ushering in the so-called Silver Age of Comics, Atlas welcomed creative dynamos like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko into the fold to become workhorses for the company in lieu of a bigger pool of staff and freelancers.

The writing was on the wall for Atlas Comics in 1957. For reasons that made sense to him, Goodman shut down his own distribution arm and threw in with American News, which subsequently closed its doors and left Atlas out in the cold. Panicked, Goodman made a poor deal with Independent News, the same distributor used by rival National, and he found himself faced with their draconian publishing parameters: only eight titles per month allowed.

In many ways Atlas’ 1957 hardships informed the coming Marvel Age of the 1960s. With only a skeleton staff on-hand, Stan Lee picked up the pencil to write even more material himself and drew Kirby and Ditko into a new publishing model that allowed for greater storytelling opportunities for artists. Goodman let the Atlas globe drop from its once lofty height to disappear from covers and make room for the explosion which readers would soon recognize as pure Marvel.

Today, Atlas Comics is remembered for a profusion of publishing and solid storytelling under the era’s duress. Short and sweet, but that’s what made it neat.

For more content about Marvel’s 80th Anniversary, visit Marvel.com/marvel80.

The Daily Bugle

Can’t-miss news and updates from across the Marvel Universe!